Gear failure complicates an unusual passage across the Gulf Stream.

St. Georges Harbor in Bermuda is a lovely place to recuperate while contemplating the passage north to New England. The Harbor is very protected and for a reasonable fee you can tie up right alongside the town square. My accommodations aboard the Fountaine Pajot Lucia 40 Catamaran I had brought up from the British Virgin Islands were quite luxurious. The three of us aboard even hosted dinner with some friends from another boat transiting north. The Wifi is pretty good too and at least once a day I downloaded updated wind and current forecasts so that I could keep an eye out for a good weather window for setting off to Newport, RI.

When you’re picking your weather window to head northward across the Gulf Stream usually you’re trying to decide how and when to best manage a low pressure system moving from west to east across your route. The systems form over the (usually south-) eastern US, often park over cape Hatteras while powering up using the thermal energy from the Gulf Stream, and then fly off Eastward – usually passing between southern New England and Bermuda. Sometimes they go far enough north to pass over New England (noreaster). Less frequently they pass as far south as Bermuda.

But this wasn’t going to be a normal passage. Leaving Bermuda Tuesday we’d be in an oddly shaped high pressure moving east. The forecast predicted a weak, oddly shaped low after crossing the Gulf Stream early Friday morning and finally another high pressure to the North as we approached Newport late Saturday into early Sunday.

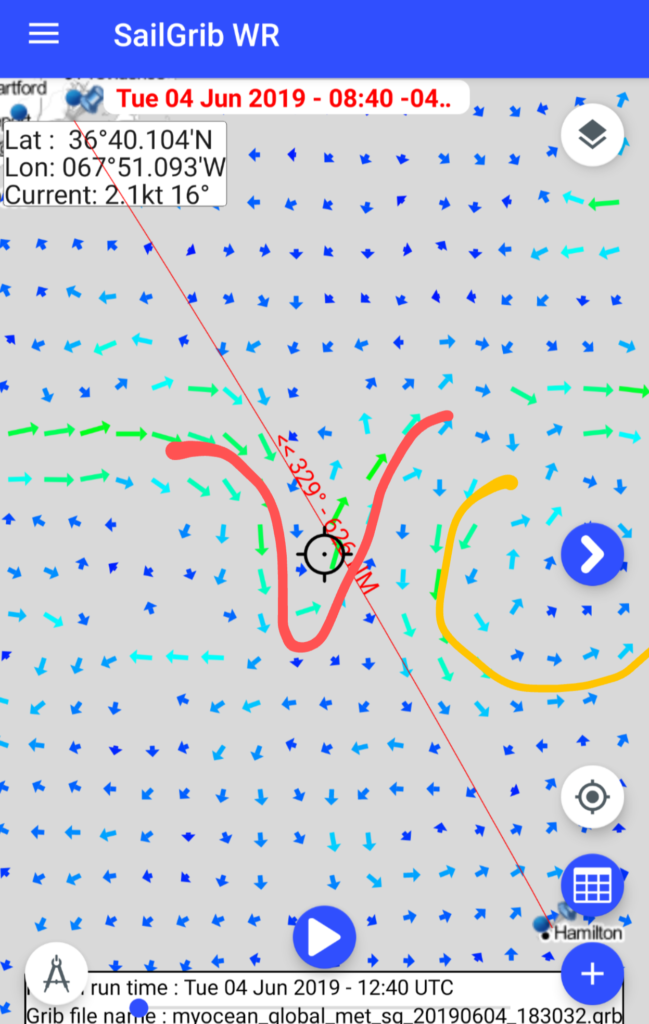

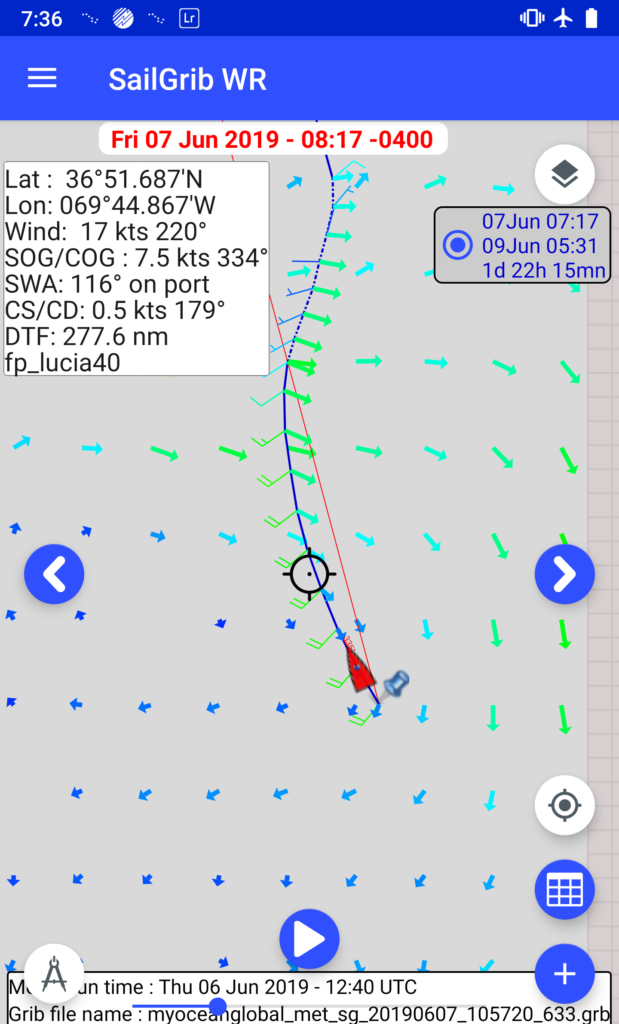

The Gulf Stream also presented us with an interesting routing decision. The rhumb line from Bermuda to Newport would put us mostly in favorable Northerly flowing current. But we’d pass quite near a strong southerly meander and another strong southerly flow from an eddy. We’d have to stay a little east of the rhumb line to avoid opposing current.

As the forecast and prevailing conditions both called for mostly South or South East winds the southerly flows would not only slow our progress northward but also would likely have larger and steeper waves where wind and current opposed. Having raced south to Bermuda several times now I’ve been out in wind against current in the Gulf Stream (when it’s the fastest way to the finish line) and knew it was certainly to be avoided on a shorthanded delivery.

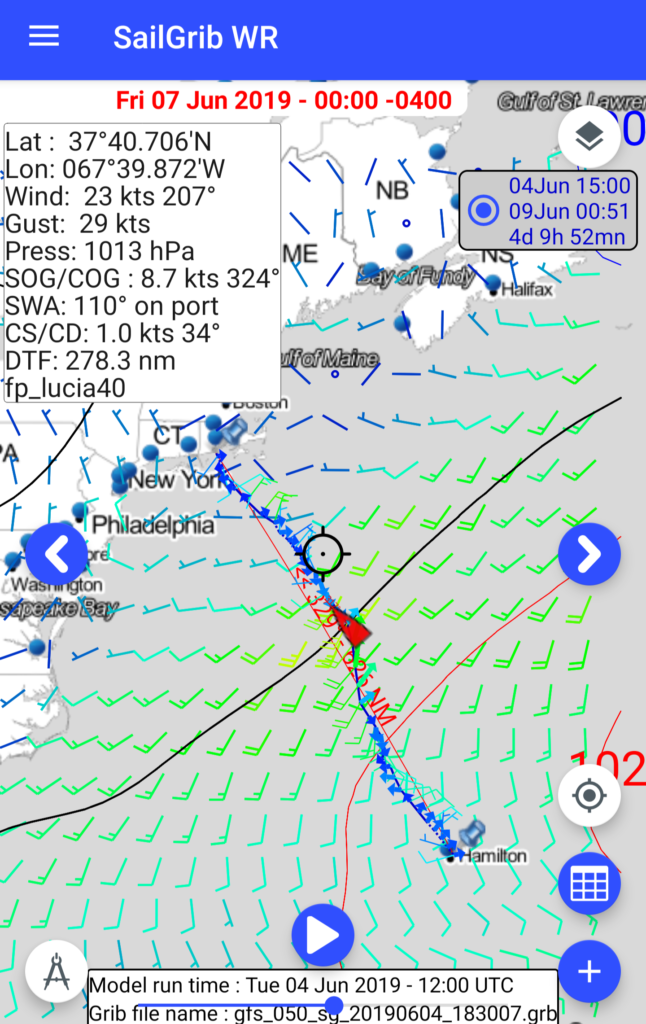

The boost of that northerly flow on the route east of the Rhumb line was tempting; get home faster and use the wind with current to flatten the seas somewhat. Unfortunately the forecast would also put us in the Gulf Stream just as the strongest winds of our passage were forecast to hit us (see figure “Tuesday Forecast 1” above). 23knots gusting 29 knots is nothing to scoff at on it’s own. Normally when I see numbers like that in a GRIB forecast I do the following math for a better estimate:

Actual Sustained Wind Expected = Forecast Gusts (FG)

= 29 knots

Actual Gusts Expected = FG + (FG - Forecast Sustained (FS))

= 29 + (29 - 23)

= 35 knots

Moreover that 29G35 would be on the beam as would the seas it generated. And with all the thermal energy from the Gulf Stream could also intensify the wind or result in localized squalls. Basically this meant that the combined wind and current forecasts closed the route east of the Rhumb line.

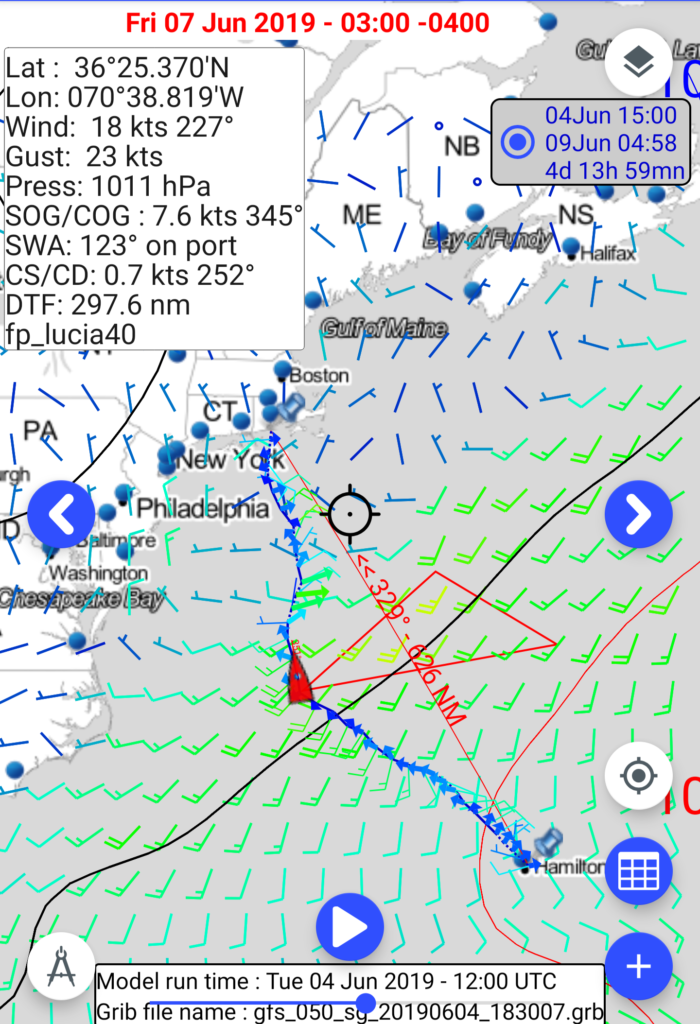

So no Rhumb line on Tuesday. No Easterly route on Tuesday. Fortunately there was another option: the westerly route. Stay west of the Rhumb line, west of the southerly Gulf Stream Meander and west of the strongest winds halfway through our passage.

So I drew a big no-go zone onto the map in SailGrib WR and pushed it’s western extent further west until I got far enough west to get numbers I liked and get us routed around all the nastiness to the east. Max wind of (18G23 translated to) 23G28 maximum aft of the beam. So apparent wind gusts maxing out in the low 20s. Not the most comfortable but certainly nothing that should be boat breaking conditions for the Lucia 40. Worst case this far off the wind with the main stowed and the jib drawing we could make slow progress without much load on the autopilot.

I also expected we’d be slower than the polars combined with the forecast would predict. This was certainly the case on the first leg of the trip and has been my usual experience with weather routing software in the past. Manufacturers polars are simply optimistic. Being behind polar projection “schedule” would mean that the strongest winds in the westerly route would race east before we got to them. I would watch the forecast as it evolved and if we needed to we could always slow down further and turn further west. Finally the westerly route built in a fair bit of searoom to run off before strong conditions before running into the southerly meander of the gulf stream.

Finally, the westerly route had us motoring through the Gulf Stream at a narrow point while becalmed. So there was no wind in the forecast to worry about the Gulf Stream intensifying.

The westerly route looked pretty good. I showed a few other captains my work and they too were convinced that a late Tuesday departure on the westerly route would be the best option. So that was the plan.

Fast Forward to Thursday Afternoon

This was one of the rare trips where we were ahead of our polar projections. I’d love to claim the credit and attribute our progress to our impressive sailing skills but what actually happened was we had slightly more wind than forecast generally from a better direction than forecast.

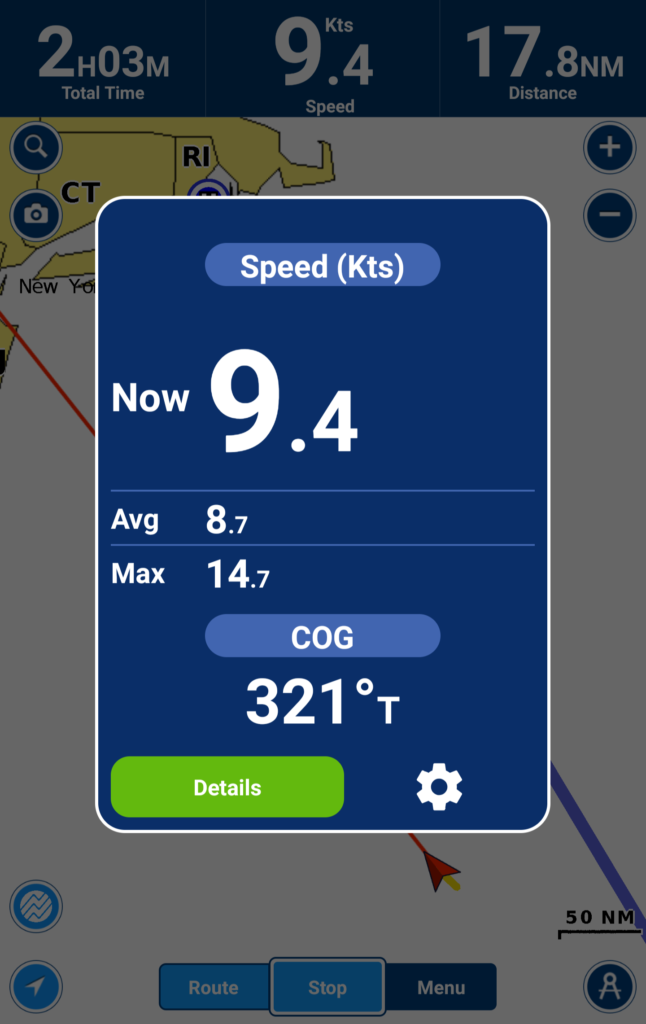

Being ahead of schedule meant we were getting into the strongest winds earlier. Thus far on Thursday we’d been setting speed records for the boat speeding toward our “turning mark” where the crew was really looking forward to bearing off and pointing at our destination instead of the Delaware Bay. The current watch was managing to average 8.7 knots SOG which put everyone in good spirits. The true wind speed was in the upper teens.

I came on watch at noon and quickly put the first reef in the main. I expected we’d reach the turning mark during my 3 hours and wasn’t in any hurry to race to the stronger winds. I also hadn’t told the crew yet but, even though the forecast had lessened to forecast:17G21 expected:21G25, I still figured it would be prudent to make more westing before bearing off into the strongest winds of our passage.

Cue the Second Reef

The wind continued to build during my watch and the apparent was right on the beam; I wasn’t ready to bear off yet. The seas were building too so I called for the crew to put in the second reef. Except

THE MAINSAIL WOULD NOT COME DOWN!

This was a stressful hour. When we realized the main was stuck the reason was not immediately apparent. We could see that the top of the main would go slack as the halyard was eased but the second or third car down would not budge. It looked as if the square top of the main had jammed the car on the mainsail track or something. We tried dropping the sail on a different tack. We tried dropping the main motoring into the wind. We tried slacking the main halyard and letting the main bounce around to perhaps shake free. We tried dropping the main using only our left hands. We tried everything we could think of.

Upon closer inspection from the leeward side the problem was immediately apparent: there was a small line from the mainsail car, around the shroud and somehow affixed to the forestay just above the jib furler.

But it was a tiny line. So I figured we could winch down on the third reef line and the mainsail was strong enough to overwhelm the line and snap it. So I started winching down on the reef line.

THIS TINY LINE DEFLECTED OUR FORESTAY AND PORT SHROUD!!

The tiny line was, of course, Dyneema. Super strong and very difficult to cut Dyneema. So we used the halyard to take the lateral load off the forestay and shroud and considered our options.

The seas were 5-7’ and building; building seas are steep. We were on a catamaran where steadying the mast using the sails doesn’t work very well. When a wave slides out from below the windward hull the boat tilts to windward and the mast is swung to windward. There was no way to send someone up the mast safely.

I tried to improvise a cutting tool using a boat hook that could be put up the mast using a halyard. But I couldn’t jury rig it in a way that would keep the swinging mast from causing the blade to slide around on the dyneema simply scratching it in different places instead of being able to cut it in one place.

We needed to put someone up the mast to cut the mainsail free. To do that we would need to find calm enough conditions to do so safely.

Since we were stuck with a sail up, the wind was building and the catamaran doesn’t point very well to begin with our options were limited. We were between 250-300NM from Bermuda at a bearing of about 130. We were 300-350NM from the east coast of the US. The TWD was 200.

We tried to point back at Bermuda. But the best we could do was 90 Course Over Ground (COG) when we needed 130. Also, don’t forget about all the nastiness that we had intended to stay west of: 90 COG meant that on starboard tack we were heading directly into that southerly meander with a strong SSW wind. Right at the 29G35. This was not a good answer.

But our navigation plan to this point had positioned us in a good place to head north. We had room to run off if necessary. We could keep Newport on the bow and the wind on the port quarter steering a course of 340. The forecast still had us crossing the Gulf Stream becalmed. If we continued heading northwest we should only encounter 21 gusting 25 (forecast 17 gusting 21). I said aloud “running off downwind, with just a single reefed mainsail up we should be OK even if the wind pipes up to 30 knots”. That was a dumb thing to say. #foreshadowing #jinxedit

Time for Hand Steering

It was too rough to cook a proper dinner so we all had snacks and tried to rest for the long night ahead. We tried to make as much westing as we could because we knew we’d need to bear off when the winds picked up.

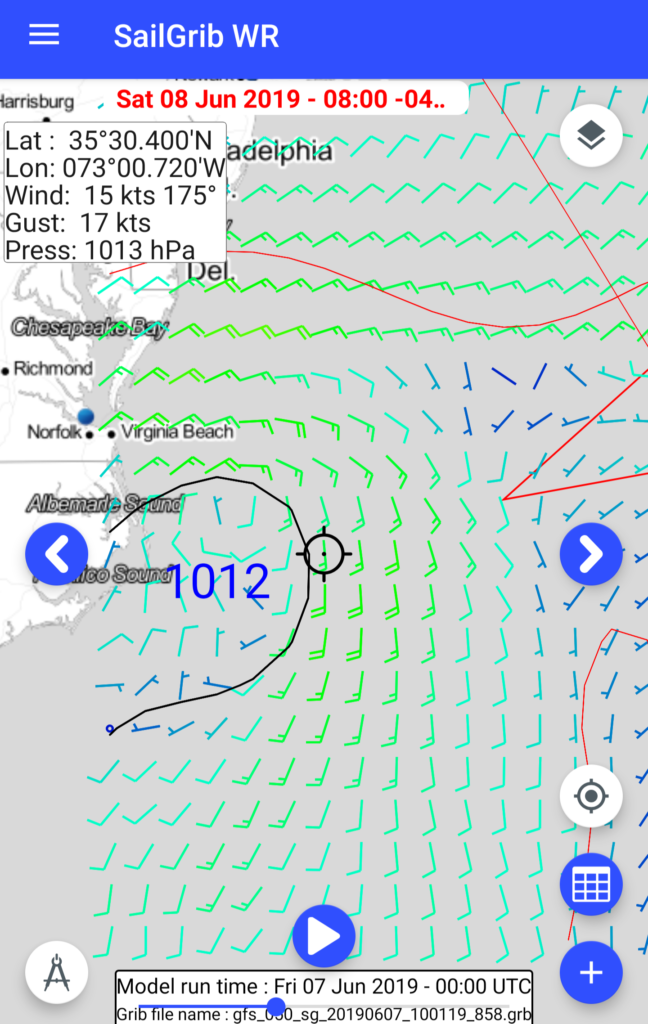

Just after sunset it really kicked up. It did not gradually build to 21 gusting 25 – that was simply, suddenly the wind we had. The seas rolling underneath us told me in no uncertain terms that we’d get more than 25 knots that night. What was worse than that was the wind was clocking: the true wind direction went from 200 to 210 to 225. Forcing us further and further east toward the southerly meander and into stronger winds.

As the wind built and we snacked on dinner and tried to rest all aboard had time to ponder our predicament. Knowing it was going to get worse and that there was nothing I could do about it was really weighing on me. I was extremely anxious. I needed something to do.

But I had something I could do. Even in the blackness and the rough sea state I could get more height out of our Lucia 40 than the auto pilot. I could drive off the surfs quickly and safely preserving the westing we had already made. It took concentration but I could keep the boat slow and high; even having a chance to glance at 32 knots of true wind and a top surfing speed of 12.6 knots. I’ve needed to hand steer in much crazier conditions so although attention and physical effort were certainly required helming did not feel extreme at all; the helm itself was actually quite light. Light enough that I was steering while seated. Ironically my hours hand steering when the winds were the strongest were the most relaxing I’d had since I looked up to see the rig deflected by that bit of dyneema line.

When I gave up the helm sometime that night the auto pilot was able to steer again and the TWD had backed to 215.

The next morning the still lighter wind had clocked to 230 and we were once again getting pushed east of North. I did a bit more hand steering on my watch trying to keep from heading east. Right around the time the sun peeked over the horizon the sustained wind dropped into the high teens and backed to 190. It was a good thing too because we had all but run out of sea room to the east. As I downloaded the morning’s forecast updates I saw this image of just how close we had gotten to being pushed into a wind vs. current thrashing:

We were definitely backed into a corner. I was really glad I had built extra searoom to run before the wind into our passage plan.

To Ascend or not to Ascend?

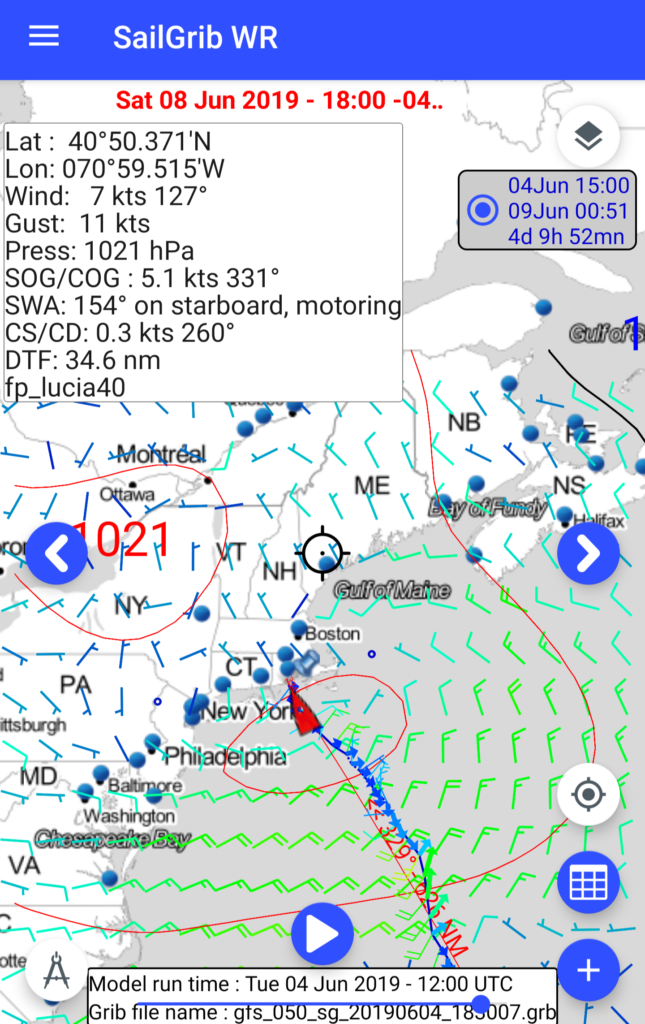

Friday the wind stayed in the mid teens as we motor-sailed across the gulf stream. It was a good day to recuperate. The southwest swell was still pretty substantial and we were getting seas from the northeast as well. The calm that was forecast was delayed until we were north of the Gulf Stream early Saturday morning. We hit a squall in the Gulf Stream that we ran off before but compared to Friday night it was tame stuff. The forecast gave us safe passage to Saturday morning’s calm.

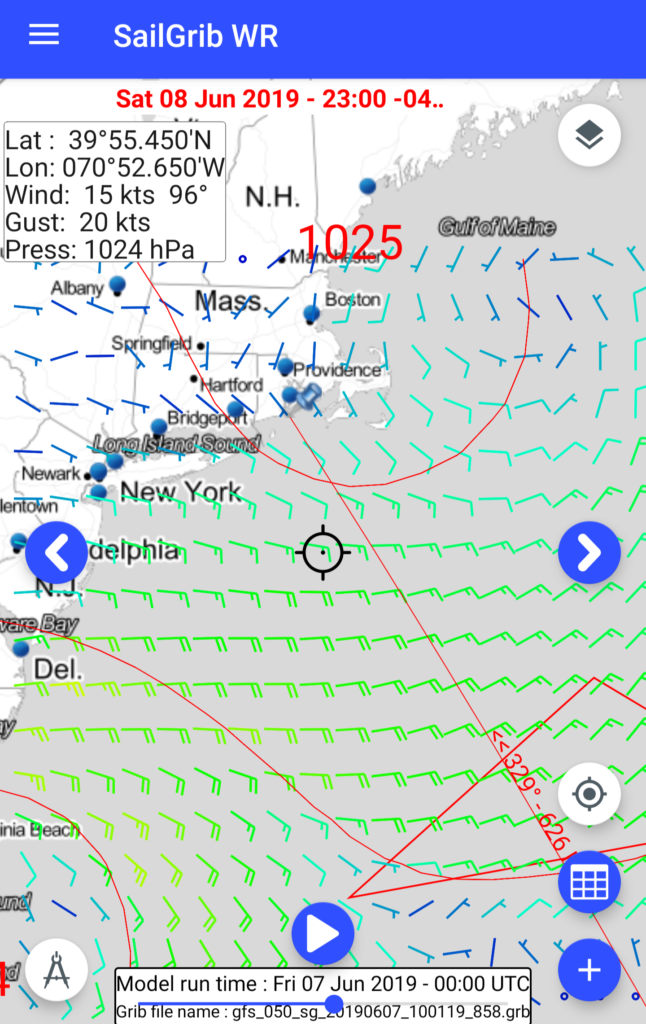

Saturday morning the vague forecast from Tuesday took shape. The weak, misshapen low pressure we were supposed to be contending with had been split in two by the high pressure that was predicted to follow it. One low pressure was too far north and East to be relevant. The other weak low pressure cell was parked over Hatteras intensifying and concentrating: getting ready to make its transit east. This low pressure would cause 1/5th of the field to retire from the Annapolis to Newport Race and dismast Prospector which was trying to set a course record. We definitely didn’t want to be there with our main stuck up when the low swept east.

Our final high pressure was well established over southeast New Hampshire and was supposed to stay there. Once we sailed through the boundary of that high pressure we’d have lightening winds eventually winding up with calms in protected Narragansett Bay when we arrived early Sunday morning.

For the purpose of the mainsail narrative all of the forecast information above was a long winded way to say that as of Saturday morning, our first conditions calm enough to safely go up the mast, the forecast called for good conditions for us to make our way to Narragansett Bay in a timely manner with a mainsail configuration stuck at reef one. So as captain I wasn’t going to force anyone to go up the mast. And nobody was volunteering. The mainsail would wait for our arrival into Narragansett Bay.

I would have gone up myself but I’m a big person and the two bosun’s chairs that we had aboard were rated for 220lbs or smaller persons. I should have checked that before we left the dock and going forward I will be bringing my own sufficiently rated ascending gear.

Back on the dock in Narragansett Bay we removed the dyneema line and the main came down fine. No permanent damage done.

Second Guessing

Given the benefit of hindsight:

- I would have removed that dyneema line before we left the dock in the British Virgin Islands. I still haven’t gotten a real answer about what it’s purpose is.

- Next time I’ll bring my mastclimber even if I know the boat has a bosun’s chair

- Continuing north once the main was stuck up was not the most conservative call but it proved to be a good enough call. I would make it again given the information I had at the time

- Our excess westing was a precaution that paid dividends

- If the forecast had actually called for gusts of 30+ knots on our route North I would have headed back to Bermuda or hove-to/feathered/motored into the wind and stayed in the lighter air. The boat and main could have taken more abuse but with a forecast of 30+, 40 knots would not have been at all improbable and then gear failures would probably have cascaded

When it comes down to it we made it successfully, none of the crew were injured, the boat made it back relatively unscathed and we all learned some valuable lessons. Heck, we even made good time catching a Jeanneau 51 that left 6 hours before we did.

Hey there, not much of a sailor really (fun with sunfish and hobies when I was younger but my family is! And your writing is terrific! I hope you’re putting a book together!! I would buy several copies!! 🙂

Great reading!!!!