As skipper and navigator just about every time we go out sailing there is “passage” evaluation and planning. Even if it’s as simple as “we have 3 hours, let’s head east for 1 hour and back west for 2” you’re always evaluating options, most of the time intuitively your head.

This evaluation gets harder as you add in unfamiliar elements. Eventually I get to the point where it makes sense to write things down and take some notes. Once that happens I like to have a checklist of considerations to go through so I don’t forget anything. I break passages up; they start with a departure followed by time underway and then an arrival. The departure and arrival require much of the same considerations so I combine their checklist:

- Departure/Exit and Arrival/Entry

- Tides & Currents

- Hazards and Obstacles

- Drawbridges with limited hours

- Special Events

- Lobster Pots in the Dark

- Dangerous sea state and current combinations

- Navigation Aids

- Presence of buoys and marks

- Lighted vs. Unlighted

- Vessel navigation gear appropriateness

- Visibility

- Tendency for fog/haze

- Daytime or Night

- Moon Phase for night entry

- Shore-side lights

- Water clarity

- Overnight options

- Moorings

- Anchoring

- Docking

- Bailout options and alternatives

- Passage & Time Under Way

- Daylight Range

- External Time limits

- Hazards and Obstacles

- Narrow passages that are only navigable with appropriate current

- Seasonal averages for hazardous weather, surprise hazardous weather

- Velocity Made Good (VMG)

- Prevailing wind strength and direction

- Swell considerations

- Motoring speed of vessel

Some of these things can’t be planned for ahead of time. Many can. The departures and arrivals tend to have more considerations simply because they tend to be in more populous waters with the complications of shore and shoal characteristics.

Really though, this is just a checklist of things to consider. Moreover, any cruising guide will repeatedly underscore potential departure and arrival challenges for a location if you don’t have a checklist handy. It gets interesting when these considerations start interacting with each other in the real world. I’ll share an interesting example: the passage from Antigua to Barbuda during our bareboat charter.

Overview

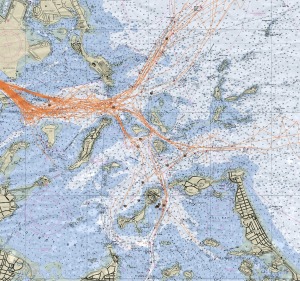

Google maps quickly told me that Barbuda is 30 nautical miles north of Antigua. My knowledge of the prevailing winds (from the pilot chart) is that it will likely be a Force 4 out of the east or northeast, so north would be somewhere above a reach but below a beat. The further east on Antigua we depart from the more free we’d be sailing.

The main constraint for the passage is daylight. When you do a bareboat the charter company generally insists you don’t sail in the dark. So I checked some almanac times and got sunrise of 6:37 and sunset at 18:06 = 11:29 = 11.5 hours. That’s plenty of time to cover 30nm that isn’t a beat. Of course we’d plan to leave early to build in a safety buffer but the overall time wouldn’t be an issue.

Next I started trying to figure out where we’d likely depart and arrive from. St. John’s on Antigua made sense for this, it was one of the northernmost harbors on Antigua and seemed well marked for an early morning departure. St. John’s has mooring, docking and anchoring options.

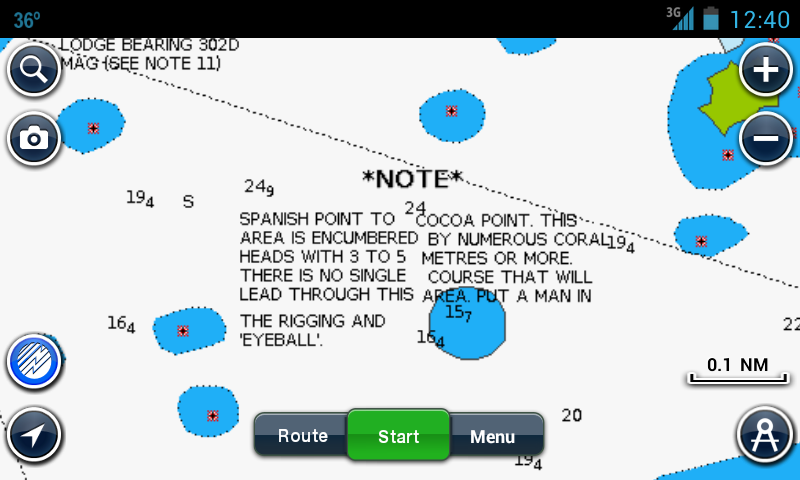

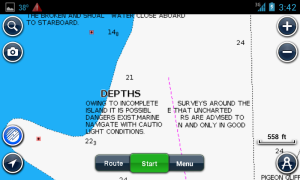

Barbuda, on the other hand, had some complications. First there are zero navigation aids. Secondly, both cruising guides indicated that charts of Barbuda are unreliable, indicating that uncharted coral heads are possible. The charts in the two cruising guides didn’t match either. My Navionics charting app of the area was also pretty clear about the fact that it is insufficient.

There are also no moorings or docking, your only option is to anchor. Normally the whole western shore of the island is protected from the east-northeast swell. If, however, there is a north swell running there are only 2 areas to anchor: Gravenor’s Bay and East of Palmetto Point. Gravenor’s Bay has a lot of coral hazards for a boat drawing 6’7” and east of Palmetto point could be impacted by prevailing swells if they come from south of east. The anchorages themselves in Gravenor’s Bay would be very cozy for a boat that draws 6’7” as well.

North swell1What is north swell? In winter large storms in the north Atlantic can result … Continue reading is always possible this time of year in the islands so it’s something to take into account. Still, we had two anchorage options that seem be suitable in most conditions, so we’d have somewhere to overnight on the hook.

The chart indicated good visibility is a necessity and the cruising guides repeated that these areas were best suited to “experienced reef navigators”. As I am not an experienced reef navigator I sought some out to figure out how best to handle these hazards; I’ve read about visual reef navigation and done some in the dinghy and as crew but am still learning.

Newbie Reef Navigating

I started talking to sailors who were my friends but I also checked out the forums over at Sailnet to see what tips they’d have for learning reef navigating. The forums were very helpful and they had a lot of tips which I’ll categorize and summarize:

- Experience and Comfort Levels

- “There is no way I can think of to learn reef navigation outside of navigating through some reefs.”

- “If you don’t feel comfortable with the situation, don’t do it.”

- “Also by taking the dinghy out a lot. And by diving the reefs.”

- Approach and Maneuvering Speed

- “All in all, stay calm, go slow and if in doubt head back to safe deep water and try again.”

- “In most ways it is not that hard as long as you are really careful and take your time.”

- “The one trick I do use is speed – the slowest possible.”

- Timing

- “Arrive between 10 am and 2 pm with the sun behind you.”

- “you want to have a high sun, preferably behind you so the glare is reduced”

- Crew Assistance

- “have one crew forward with a good measure of common sense”

- “they talk about going up to the spreaders to look”

- “stand on top of the windlass”

- Electronics and Gear

- “when you are going in turn on a track on your plotter, it helps when you are coming out and visibility might not be so good”

- “use all the gizmos I have including Google Earth cached images as well as my eyes on full beam”

- “you want polarized sunglasses”

- Contingencies

- “reverse off QUICKLY.”

- “If I get disoriented, or a bit unsure, I head back out and do it again”

Somebody even mentioned visiting the anchorage I mentioned “on a boat that drew 7 feet – it was a very slow go getting in and out.” “In good light conditions the Gravenor’s Bay anchorages are easy to access with the reefs and coral heads standing out clearly.” It was suggested that this anchorage is forbidden by most charter companies as well which we looked into and might hear more about in our briefing.

But for now I’d say we’re still a go, albeit very carefully and with all the Gizmos I can muster. Including my handheld depth sounder and the dinghy.

Reconsidering the Passage

The overhead sun requirement for effective reef navigating does change the way we’ll need to approach the passage. If you need to arrive when the sun is overhead we’ve only got half the daylight or 5.75 hours (instead of 11.5). That’s 5.5 knots VMG which requires a bit more wind but is entirely doable. It does mean getting up really early and probably making sure to pick a windier day. Furthermore the desire for flat water when reef navigating directly conflicts with the desire for a bit more wind to sail to Barbuda.

So, an early departure to arrive at a destination with unmarked and unreliably charted anchorages without guaranteed protection. That I’ve never visited before. In an unfamiliar vessel. Right at the edge of my limit but no definite “don’t go” flags. We’ll try to find a day to give it a go but certainly reserve the option to bail at any point. There is a lot to wait and see about and ultimately we won’t make the final decision to go until we’re there.

There is also a lot of opportunity for reef navigation practice in Antigua, there are plenty of areas in Antigua that the charts note “uncharted hazards” along with plenty of areas with charted reefs as well. By the end of this passage I don’t think I’ll be a newbie reef navigator anymore 🙂

Generally Speaking

As you see here, the dominating consideration is the unfamiliar arrival. Often you wind up working backwards from ideal arrival conditions when visiting a new destination. Departures are usually more familiar (you’ve usually already entered and have all the time you like to orient yourself). When going somewhere familiar other considerations take priority.

I start with that checklist, figure out most important considerations and then balance them to the best of my ability. Usually for familiar waters this happens almost by reflex.

Have any other considerations that didn’t make my checklist? Please share them here or in the comments!

UPDATE: Curious how this passage went? Find out here!

References

| ↑1 | What is north swell? In winter large storms in the north Atlantic can result in large seas traveling south to the islands and making many anchorages untenable |

|---|

Leave a Reply