Mr. Safety nudges you toward the Danger Zone

Dana called me out, loudly, “if there is anyone who embodies one of the stereotypes in that video it’s you; you’re ‘Mr. Safety.'” We were at the bar after an uneventful evening circling cans and haranguing each other using the latest sailing video to make the rounds. I laughed along but I couldn’t disagree; of all of my experienced friends I’m the most safety conscious.

That same night I got a call about a delivery that would probably include sailing offshore through a gale. This would be my second gale. We’d also be shorthanded with a crew that I had never met on a boat that I had never been aboard. After assessing the situation I signed myself up.

“Mr. Safety indeed” I thought to myself. As I started packing I realized this wasn’t a contradiction at all; my focus on safety and preparation enables me to sign on for adventures like this on short notice. I trust my skills, gear and preparation enough to head out there and have confidence that I’ll overcome the adversity encountered at sea.

Survival Priorities

Concussions, broken bones, cracked ribs and lacerations: all potential trips to the emergency room; all safety concerns. But when it comes to safety at sea the stakes are higher: you’re main concern is survival; cuts and bruises are a distant second. When I consider safety at sea I always work backwards from survival (though Mr Safety always brings a first aid kit). Here is where I start:

Good decision making in survival situations demands a simple framework for prioritizing dangers. One that has been drilled into me as I learned about survival and first aid was the Rule of Threes. I’ve heard it a few different ways but it basically boils down to this:

In extreme conditions you can survive for:

- 3 minutes without air

- 3 hours without shelter

- 3 days without water

- 3 weeks without food

These values are approximations and situation dependent but they quickly rank your survival priorities by orders of magnitude. One unfortunate adjustment for the marine environment is that hypothermia takes hold of you much faster if you’re in cold water than in cold air. If you’re floating in cold water without a flotation aid you’ll drown within minutes. Immersed in cold water, with a flotation aid, you’ll be overcome by hypothermia within an hour. For our purposes the amount of time you can survive in the sea without shelter is measured in minutes, not hours.

If you’re offshore you’re generally hours if not days from aid. In an emergency situation at sea where you’re able to contact assistance this means you have to provide your own air and shelter until assistance arrives. At sea air and shelter are provided by a single mechanism: the boat!

Take care of the boat and it will take care of you

If you can take care of the boat it can take care of you. When I’m deciding whether or not to go on a sailing adventure the main thing I am assessing is whether or not I’m prepared to sail the boat I’m aboard to safety:

- in the worst conditions reasonably anticipated

- with little or no assistance from others aboard

- if all of the boats electronic and engine powered systems fail

This is a pretty high bar. Unfortunately, each of these eventualities have happened to me on their own; it’s not a huge stretch for all of them to happen at the same time. That risk is exacerbated when I sign on to a trip with unknown crew on an unfamiliar vessel. Setting the bar any lower this early in the process would be foolish.

I’m not worrying about sailing the boat well and getting her where she’s going without a scratch. Maybe it takes twice as long. Maybe we only use the headsail or only use the mainsail. Maybe we motor the whole way. Maybe we divert to a nearby safe harbor. Maybe the closest I can get to the destination is a nearby anchorage.

My goal isn’t to have to resort to any of these measures. My objective is to prevent any of these measures from becoming necessary; however when you start talking survival they’re all on the table.

Sailing to safety involves two main activities: navigating and operating the boat.

“May all our landfalls be expected”

They say “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”. At sea navigation is that prevention: navigation is the art of keeping your vessel clear of trouble while getting where you’re going.

These days the tools available for navigation are portable, inexpensive and make keeping out of trouble easier than ever – but only if you prepare correctly!

Preparing your backup handheld, self contained, waterproof navigation station

With the right inexpensive upgrades your smartphone is a handheld navigating dynamo. Download charts for the areas that you’ll be sailing. Download charts for areas that you’ll pass by while sailing. Download charts for any areas that you could possibly have to divert to while sailing. MAKE SURE THESE CHARTS ARE DOWNLOADED and not just accessible when your phone is connected to the network.

Looking for more? Start here with my Smartphone navigation guide!

Navigation Review

At this point I’m assuming you’re familiar with navigating using your chartplotter app of choice. If not you’re probably not ready to skipper a trip on an unfamiliar boat with unfamiliar navigation gear with unfamiliar crew. If your circumstances are more accommodating excellent: proceed with this review and and pretend they aren’t; consider this a learning opportunity.

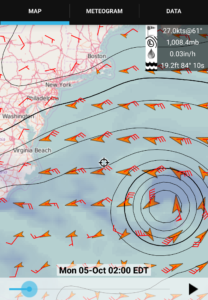

First download the GRIB forecast for the area you’ll be navigating. Update the charts on your phone for the area you’ll be navigating.

Before you dive in activate airplane mode on your phone! Now if you didn’t download something you’ll find out while you can still connect instead of when you’re at sea and you need it and can’t download it.

Find your departure port. Find your arrival port. Find any anticipated stopover ports. Plot a route that you could take. Double check that route. Investigate potential harbors of refuge along the way. Investigate potential hazards along the way. Check your route against the GRIB forecast.

Check the pilot charts for the area. (you can turn off airplane mode now.) Google “navigating body of water that you’ll be navigating”. Ask the rest of the crew if there are any concerning parts of the passage.

Your navigation review should give you a sense about how adventurous the trip could be. You should have a good idea about what the biggest hazards are, how far you’ll be from harbors of refuge, what the conditions could be like. At this point you can make a much more educated assessment of how your skills and experience measure up to the adventure and anticipated conditions.

More on Navigation

I’ve done ocean passages where I had my phone turned off the entire time but that is the exception rather than the rule. Whenever I have doubts I check and double check the navs with gear I am familiar with. This guarantees I have the necessary data downloaded ahead of time and the added navigation checks add to our safety margin.

The above is only a quick rundown of the navigation preparations I use to evaluate a potential sailing adventure. SavvySalt will cover navigation in much more depth in the future. Join the community here to be notified when we do.

Piloting the boat where you’re going

Unless things have really gone off the rails navigating and operating the boat according to plan are the two key challenges of sailing adventures. We aren’t worried about the stereo or the microwave; we just need to get the boat to go where we intend under sail or under power: “piloting” collectively. Piloting the boat can be divided into two separate but equally important parts:

Propulsion

A sailor on a sailboat with an auxiliary diesel has lots of tools for propelling the boat; in sailing the primary activity aboard is making the sails drive the boat. There are at least two sails, often many more that can be used to keep way on. There is the diesel engine. There are combinations of the diesel and sails.

The sails and diesel are basically redundant systems for propulsion: if one isn’t working you use the other. If you’ve got a small diesel and the wind has cranked up to 30+ on the nose and you can’t motor it into it you roll out some jib. If the diesel dies you sail. If the wind dies you motor. The range of the diesel is an important constraint but not often a limiting one. Top up the tanks anyway.

To Mr. Safety this redundancy is a useful safety feature; especially because I don’t know much about repairing diesel engines or masts.

Steering

Steering aboard a monohull sailing yacht is not redundant. Not being able to propel the boat where you want it to go is a small problem when compared with losing steering control whereupon the boat may wind up somewhere dangerous. Not being able to control the orientation of the boat at all in dangerous seas could turn a trying situation into a life threatening situation.

The additional steering gear aboard is the second thing I check when I’m come aboard a boat I am adventuring aboard. Where is the emergency tiller? Is there an emergency rudder? Is the autopilot control of the rudder separate from the steering wheel(s)? If there are twin wheels are they independently attached to the rudderpost? There is often redundancy and emergency gear for turning the rudder. If there isn’t I might reconsider the trip.

If the rudder itself fails you’re trying to improvise steering; possibly complicated by what’s left of the existing rudder turning the boat in whichever direction it pleases. The mechanism behind an improvised rudder is simple but the loads involved on larger boats make successful improvisation difficult. Add in large and/or confused seas and your efforts at makeshift steering may be futile.

I’ve been offshore two different times where I’ve felt something in the steering give way and it’s always a very unnerving feeling. One time some gear that got loose needed to be cleared out of the steering mechanism. The other time we never found the problem and it didn’t bother us again.

When you’re not going to get where you’re going

If you’re in a situation where you doubt you’ll get where you intended to go start with the threes: if you have them you’re not in immediate danger. If you still have the boat you’ve got air and shelter. You’ve probably got water and in all likelihood you have food you don’t need. You need to figure out how much time you have before the situation becomes dangerous and how to receive assistance before it does.

Any port in a calm!

My buddies and I decided to kick off a season by taking a J/29 from Boston to Provincetown and back. The trip back started at first light with two reefs and a favored tack taking us due north. Six hours later we were becalmed 20nm from Boston and started up the outboard. Being our first trip on this boat we didn’t have much of a sense what our outboard’s range would be with the 5 gallons of gasoline we had; we started to doubt we could make it to Boston.

We cut the motor to conserve limited resources and evaluated our options. The first thing emphasized is that we were in little danger. We had all the threes: air, the shelter of the boat, water that we had brought and even plenty of leftover food. We were far from any hazards that could threaten the boat. We were within VHF range. We could wait it out.

(We wound up diverting to a closer harbor. And the wind filled in as the VHF robot voice predicted it would. And we had enough gas to make it to Boston anyway.)

Emergency Food and Water:

Mr Safety brings some emergency water. 2 or 4 litres in a convenient reusable container that is easy to fly with and fill up near in the departure port. Delicious!

As a rule my trips are over provisioned which is good but I’ve been on under provisioned trips. When Mr. Safety is unsure he brings a bunch of cliff bars. And Cheez-its. It’s never been a safety need but fed people make better decisions. And Cheez-its are delicious!

The water buys days, not weeks. The food doesn’t buy any safety margin but it does make waiting far more comfortable.

Communicating with Assistance

So you’re safe aboard a boat. The only thing you need other than the threes is a method to communicate so that your can arrange assistance (this isn’t rescue, you’re far from imminent danger).

Do you plan to be in VHF range the whole trip (roughly 20nm from shore in US waters)? Cell phone range? Does the boat have a sat phone? Make a test call. Shortwave Ham or SSB Radio? I hope you know how to use that thing…

These days most of the essential communications gear is handheld and provided by the skipper. Ask for the satellite phone number, say it’s for your parents or significant other in case of emergencies. Even if you have your own sat phone. If there is no such number be weary. Find out how many EPIRBs will be aboard? There should be one for each life raft at least. Find out if there are Personal EPIRBs aboard that you can use.

Mr. Safety has a handheld VHF radio stored with the battery taken out for emergencies. Mr. Safety has a smartphone navigation system and and backup tablet or smartphone; though when you’re out there VHF usually proves much more effective. Mr. Safety has a Delorme InReach 2-way satellite messaging device. He’s also got a Personal EPIRB (affiliate link) which is absolutely a last resort in these circumstances.

Once you’re in contact with aid you’ll work out the assistance you need to get the boat and/or crew ashore before survival is an issue. Maybe you need a tow. Maybe you need some fuel or water dropped off. Heck maybe you just need somebody to google “9.9hp outboard engine gallons per hour”. No matter what if you’ve got the the threes and a way to communicate with assistance you’re going to work it out.

Leaving the Boat Urgently

You could hit a UFO (Unidentified Floating Object). A whale might attack your boat. The hull could fail below the water line. This is a true survival situation. Your only course of action is to contact rescuers, give them your location and stay alive until they arrive. Once you allow for these remote possibilities you need a plan to survive when the boat becomes unable to provide you with air and shelter.

This isn’t entirely a bad thing. It takes days if not weeks to determine if a boat is ready for an offshore passage (local copy). It’s better and far more feasible to plan for the worst; especially remotely.

We already discussed contacting assistance. When you might lose the boat portability and immerse-ability become paramount. First on your list should be all the EPIRBs. Then all other communication equipment that is portable.

Stay with the boat until you can’t! When to leave a boat can be difficult to determine, very situation dependent and beyond the scope of this article. I want to emphasize, however, that if you can stay in (or with) the boat should seriously consider it.

Stay with the boat

Air and shelter, your two highest survival priorities, are provided by the boat. If you get separated from the boat your air and shelter are in jeopardy; you are in a survival situation. The tried and true way to prevent this from happening is the jacklines, tether and harness system.

You should have your own harness and tether. Mr Safety recommends a double tether and an inflatable PFD with integral harness.

When you get aboard ask where the jacklines are and/or if they’d like you to run them. There are lots of nice to have considerations for jacklines but as long as they complete a system that allows you to get anywhere on deck while tied to the boat you’re covered.

Medical Assistance

Medical aid is one reason that a crew-member might need to leave the boat urgently. A crew member requiring medical assistance complicates your survival priorities; when you need medical assistance it can be a higher priority than remaining with the shelter of the boat.

We’ve already covered your options for contacting assistance ashore. In the case of a medical emergency buying time becomes more complicated than remaining aboard a floating boat: first aid will have to be administered and will be limited by the amount of first aid training and equipment onboard.

A certain number of Red Cross trained crew is a requirement for most offshore races. The medical kit required by the Offshore Racing Rule (ORR) is extensive enough that the limiting factor will almost certainly be medical training onboard. This is where a satellite phone shines above and beyond EPIRBs and satellite data devices: medical professionals ashore can walk you through medical procedures over the phone much more easily than via email.

Mr Safety always brings a small first aid kit but is well aware that it is very limited. If you have any medical conditions Mr. Safety strongly suggests you not only bring any specialized medication or equipment (including instructions!) for treating all complications of that condition but also inform the crew before departure so they might familiarize themselves with the care that might become necessary.

If you have a medical condition you will most likely be the expert aboard on how to deal with it’s complications. Other than that, short of an EMT, paramedic or doctor aboard it’s very difficult to judge a passage’s preparation for medical emergencies that may arise. Even with a doctor aboard, when you get down to brass tacks, “truly life threatening injuries or medical conditions are unlikely to be treated successfully offshore, even with a physician onboard. A successful Heimlich maneuver for upper airway obstruction or mouth to mouth resuscitation for drowning may be exceptions.”

Staying afloat without your boat

A life raft greatly increases your chances of survival. It’s the closest thing to a backup boat you can have aboard. Unfortunately they are impractical to travel with and impossible to fly with. Mr Safety always makes sure there will be a life raft aboard if we will be outside VHF range; all of the satellite communication options take far longer to summon aid.

There are personal life rafts that you probably can’t take on a commercial flight. You can take an immersion survival suit on a flight but they’re bulky. A dinghy can be used as a life raft in a pinch. Mr. Safety is considering buying a drysuit (affiliate link) for on deck conditions that are too extreme for foulies, extra overboard protection and situations where ditching the boat becomes necessary.

Any true offshore life raft needs to be provided by the skipper or the boat. It must hold a current certificate of inspection; these certificates of inspection can only be provided by a certified inspector.

None of these options should be considered rescue; all they can do is prolong your survival time until rescue can reach you. A full size life raft is the best of these bad options; don’t consider getting into a life raft as an escape from peril: at best you’re exchanging one form of peril for another.

The Ditch Bag

The other thing that goes with you when you ditch the boat is the “ditch bag”. When you sign on for a passage the skipper will likely have a ditch bag prepared; make sure by asking which important paperwork the skipper will need copies of for the ditch bag.

Mr Safety’s 90 liter dry bag (affiliate link) doubles as a ditch bag. Recalling the threes Mr. Safety keeps the emergency water and emergency food in the dry bag. The bag itself is airtight and can be used to float further above the water to slow the onset of hypothermia. Toward this end when feasible Mr. Safety moves non-survival gear out of the dry bag when getting settled. Mr. Safety keeps all of his emergency communications gear in the ditch bag (except his Personal EPIRB which is kept on his person). Mr. Safety doesn’t bring flares or other pyrotechnics but always has a whistle, a mirror and an extra submersible flashlight inside. The extra clothes inside could also be put to use for keeping warm or sun protection.

Mr Safety’s 90 liter dry bag (affiliate link) doubles as a ditch bag. Recalling the threes Mr. Safety keeps the emergency water and emergency food in the dry bag. The bag itself is airtight and can be used to float further above the water to slow the onset of hypothermia. Toward this end when feasible Mr. Safety moves non-survival gear out of the dry bag when getting settled. Mr. Safety keeps all of his emergency communications gear in the ditch bag (except his Personal EPIRB which is kept on his person). Mr. Safety doesn’t bring flares or other pyrotechnics but always has a whistle, a mirror and an extra submersible flashlight inside. The extra clothes inside could also be put to use for keeping warm or sun protection.

The Outlook on Safety

We’ve considered some very dire situations; I understand if you’re more apprehensive now than when you started. But I am reassured by what has been said here. As pick up crew on a passage you can bring your own ditch bag; a ditch bag that provides two of the threes and helps with the other two. You can provide your own immersion gear, up to and including a personal life raft! You can bring your own gear that all but ensures you stay with the boat.

You can provide your own state of the art gear communication gear for summoning assistance.

Most importantly you can bring a handheld, self-powered, waterproof navigation station that enables a competent seaman to predict and avoid most perilous situations long before they are upon you.

Every sailboat has redundant propulsion and many have partially redundant steering. Unfortunately you can’t pack an emergency rudder.

These nearly comprehensive capabilities have only become available to crew in the last decade. It’s an exciting time to be a crew: through your own preparations you can all but ensure that the excitement is due to the passage itself and not insufficient preparation.

Short Safety Checklist

- Preparation crew can ensure

- A full navigation review of the passage planned

- The ability to pilot the boat safely

- A Complete Suite of Handheld Navigation Tools

- Personal Safety Gear

- Ability to communicate with shore: Personal EPIRB (affiliate link) and Satellite Phone and/or Communicator

- Waterproof ditch bag with water, food and basic first aid

- Preparation crew should investigate

- Life Raft & Ditch Bag

- First Aid Equipment and Training

- Boat safety gear – especially that the navigation review deems prudent

- Boat and skipper communication gear

Starting the passage evaluation conversation:

Now that you have this whole framework to evaluate passage safety how do you start gathering the necessary information? I usually start my safety evaluation via email; I like having this stuff in writing and it’s usually the easiest way to reach busy sailors.

Here is a condensed version of my most recent passage evaluation with a professional skipper (we’ll call him Paul here) about delivering a recently sold racing yacht from Boston to Halifax. I’ve been offshore with Paul before. My navigation review indicated that we’d probably encounter Maine’s notorious fog so AIS and/or radar seemed prudent. The boat was also easy to research via the internet because we had access to the new owner’s pre-purchase survey.

Hey Paul,

Sounds like a fun, possibly very cold, adventure!

Is your satellite phone number still [omitted]? Do you still have that copy of my passport for the ditch bag?

The listing indicates offshore racing safety gear. We should see if the broker or owner can send us a pic of the liferaft’s inspection certificate; otherwise we’ll be lugging your “portable” liferaft around once again.

Since the survey says the boat will need new electronics and doesn’t mention AIS or radar we should see if the owner would be amenable to upgrading the VHF to a model with built-in AIS receiver. Too bad the VHF + AIS Transmitter hasn’t been released yet; that would be even more reassuring in the fog.

The lack of autohelm will be annoying but with all the questions about the electronics I would have wanted enough crew aboard that we’re not dependent on the autopilot anyway. The rest of the essential electronics we’ll have at least half a dozen handheld backups; they’ll probably be fine but no worries if they’re not. I might actually get to use my handheld depth sounder this season 🙂

Anyway, keep in the loop and I’ll keep an eye on return flights,

-TJ

Any skipper that you want to sail with is going to be eager to have crew aboard who are aware enough to ask these types of questions. If they’re not that’s a clue you might want to reconsider the passage.

Once you start the conversation you’ll learn a lot especially if you google or ask around about the things that come up that you’re not familiar with. One last thing is don’t hesitate to share your passage evaluation with other sailors you trust. They could catch important things you’ve missed. If you’re really stuck you can reach out to me.

So talk to your skipper and get out there!

Updated 30-Nov-2019

Leave a Reply